My research into my grandmother’s ancestry has led to the discovery of a number of Thames watermen who plied their trade between the mid-seventeeth and early nineteenth centuries. All of them were ancestors of my grandmother’s great-great grandmother, Eliza Lucy Rudland (1816-1865) who was from a long line of Kentish families. I have been able to confirm 24 watermen individuals so far, but it is likely that there were many more as it was normal for generations of men and boys to be employed in the same profession.

The river Thames has always been a key highway in London, with people and goods travelling along and across it. Until the early eighteenth century, London Bridge was the only crossing so boats were vital. Watermen operated wherries, barges and ferries to transport passengers on the river, and would gather at the various steps along the Thames waiting to be hired. They were the taxi drivers of their day. Watermen were generally considered to be “rough and ready”, known for their coarse language. Crime, overcharging and overcrowding of vessels were issues, so, in 1555, an Act was introduced to regulate watermen activities and introduced apprenticeships for boys from age 14, who thereafter became members of The Company of Watermen and Lightermen of the River Thames.

Life for watermen could be tough. While some were reasonably well off and could afford their own vessels, many were poor and struggled to make ends meet. Most would need to tout for business though some may be lucky enough to secure regular work from a wealthy gentleman or merchant. In Putney, watermen set up their own charity to support poor families, including the widows of watermen who had died in the Thames or at sea – for some this was a natural next step, though press gangs were also a risk. It is perhaps not surprising that the waterman strongly contested proposals to build a new bridge across the Thames, a direct threat to business, though they were ultimately unsuccessful.

Our watermen ancestry mainly consists of 3 large families in the south-west London area, who intermarried. The Bemish (or Beamish), Sears and Meredith families all appear frequently as court attendees in the court rolls for Wimbledon in the seventeenth century, so it is likely that they were tenants of the local manorial lands. I have traced the Bemish family back to a gardener, William, who lived in Mortlake and was my 9 x great grandfather. In 1708, William Bemish (-1756) married Anne Sears (1688 – 1747) from a Putney family. Anne’s grandfather (my 11 x great grandfather) was Michael Sears ( – 1717) who was a waterman, as was her father John Sears (1662-1729), and two of her brothers – another Michael and another John, both of whom were apprenticed to learn the trade from their father.

William and Anne had eleven children, of which four sons definitely became watermen. The eldest, Richard Bemish, was apprenticed to his uncle John Sears but it appears that he died soon after. Although the circumstances are not known, drowning was a risk for watermen. John Sears also trained up two more of his nephews, William Bemish (1714-1783), my 8x great grandfather, and Thomas. Another Bemish brother, Charles, also became a waterman, as did his son.

The earliest waterman I have found was a 10x great grandfather, Samuel Meredith (1638-1704) who lived and worked in Mortlake, now the site of the finish line for the Oxford and Cambridge boat race. Samuel and his wife Martha Ludgall (1641-1712) had eight children, at least two of whom became watermen. The older son, James Meredith (1665-1716) appears to have obtained a higher social status, becoming a Royal Waterman under King William III and named in the Establishment List for the Royal Household in 1688-9. James would have been responsible for rowing and maintaining the Royal Barge and transporting the King and his family along the river; very different to the daily work of the rest of our watermen relatives!

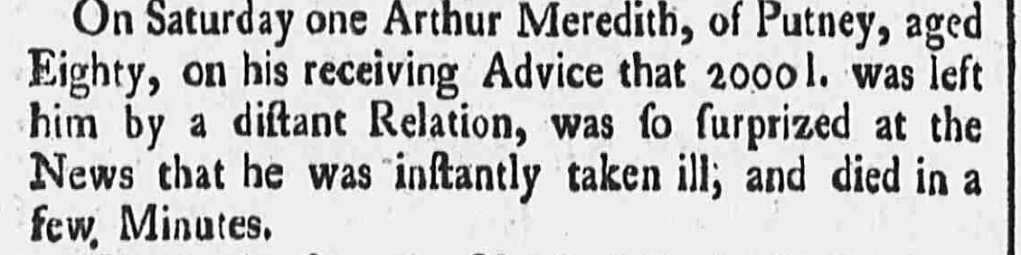

James’ younger brother, Arthur Meredith (1676 – 1754), my 9x great grandfather, was apprenticed to his father Samuel in Mortlake at the age of 15. He married Margaret Calverley (1683 – 1738) and the couple had eight children, moving to Putney at some point between 1716 and 1720. Arthur seems to have been of good standing in his community, he is recorded as Head of a Tithing (sub division of a parish) in Putney in 1739, giving him responsibility for maintaining law and order. The family were not wealthy though and we know that Arthur borrowed money from his father-in-law Matthew Calverley (1645-1728) who refused to leave anything additional to his daughter’s family in his will. This may explain Arthur’s reaction to a more generous benefactor, which ultimately led to him achieving fame in death, reported in at least six newspapers around the country:

Sadly, I have not yet been able to identify Arthur’s distant relation but will keep searching!

One of Arthur’s sons, another Arthur, became a mariner – working as part of a crew of a vessel. He was serving on HMS Worcester when he died in 1743. A daughter, Mary, married John Henshall who was a lighterman working in Westminster; lightermen carried goods rather than passengers. We are descended from Arthur’s fifth child, Martha Meredith (1716 – 1775) who, in 1737, married William Bemish (1714-1783).

William and Martha remained in Putney, where they raised eight children. All five of their sons became apprentice watermen, four of them trained by William himself. Unfortunately I have not been able to trace all of them into adulthood, despite one of them having the distinctive name of Thomas Christmas Bemish (we can guess when his birthday was)! William did have at least one grandson, John, who followed the previous five generations into the profession.

There is also another branch of watermen within my grandmother’s ancestry who appear to be separate from the Bemish, Sears and Meredith families. Thomas Wilson (?1734 – 1804) lived in Greenwich, where he was a collegeman, using a type of flat-bottomed barge. At least two of his three sons followed in his footsteps, and his son James was apprenticed to him in 1791. The Wilson family would have been directly impacted by the development of docks in Greenwich, which led to rivalry between local ferries and fears that lightermen would lose business.

Although the dock developments and the building of multiple bridges across the Thames have vastly reduced the number of watermen working on the river, the profession and guild still exist and apprentices are still trained to operate vessels safely on the river.

Hi Ruth,

I am really interested in this as each year when we row in the Great River Race, the certificate we receive is from the Company of Watermen and Lightermen of the River Thames. So it’s therefore interesting to see the Rosie’s side of the family linked back to them.

Thanks for the update

Hope you are all well

Love Richard

________________________________

LikeLike