It isn’t often that I have been able to find physical items belonging to my ancestors; even gravestones have proved elusive! However, there are several items in existence which were handcrafted by my 8 x great grandfather, George Hobart (1692 – ?), who worked as a clock and watchmaker in London in the first half of the eighteenth century.

George’s family has been difficult to trace, partly due to the variations of spelling (Hubert, Hubbard to name a couple), but we know that he was the son of another George, a Gentleman who lived at least part of his life in the Aldgate area of London. George junior was apprenticed in July 1707 to Jonathan Rant, a well-known clockmaker in the city. George would have been around 14 years old when he started his apprenticeship, and became “free” on 2nd September 1717, ten years later. Completion of the apprenticeship meant that George became a Freeman (citizen) of the City of London, as he was inaugurated into the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers. Only two weeks later, George took on his own apprentice, himself the son of a clockmaker, suggesting that George’s work was respected.

At some point during his own apprenticeship, George had married Elizabeth, and the couple started a family. Three of their nine children were born during George’s training period. The family initially lived in Wapping, before moving to Clerkenwell, the centre of watchmaking in London. The late seventeenth century had seen an influx of skilled French watchmakers who were escaping Huguenot persecution; perhaps the Hobart (Hubert?) family even had its origins in France.

Watchmaking was a profession with close links to other metal work, i.e. blacksmithing and silver and goldsmithing. Apprentices learned to file and shape hard wood before moving on to work with metal. The watchmaker would have used a lens to undertake finely-detailed work, working on mechanisms for many hours. An 1881 publication, The Watchmakers’ Handbook, listed eye strain, conjunctivitis and irritability as some of the health hazards of the profession.

George’s work ranged from small pocket-watches to large clocks that would have graced eighteenth-century parlours. In 2008, this silver pocket-watch was sold by the Bonham’s auction house for just over £2,000. The watch dates from around 1720, relatively early in George’s career.

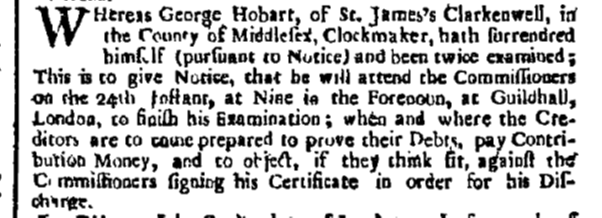

Unfortunately, despite the quality of his work, money was tight for the Hobarts, and there were many mouths to feed. A newspaper article published in September 1722 shows that George was threatened with bankruptcy and was being chased for payment by a number of people.

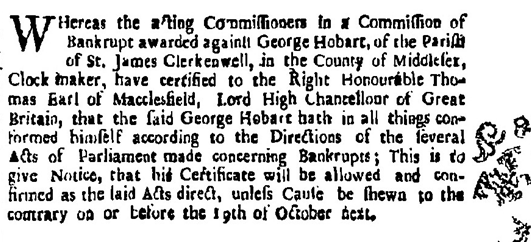

On this occasion, George was able to raise the money and another article later that month confirmed that his certificate of discharge from bankruptcy had been approved, freeing him from restrictions.

George continued to work. To make clocks, he would have worked in collaboration with a cabinet maker, though only his name would have appeared on the finished piece. A beautiful example of a longcase clock made by George around 1730 is currently for sale, if anyone would like to own a genuine piece of family history!

The family moved to the east end of London but sadly, George’s money struggles continued and worsened. By 1737 his creditors had caught up with him, and he was bankrupt and in the infamous Fleet debtors’ prison. The Fleet was situated off Farringdon Street in London and dated back centuries, though was by this time only used for debtors, who paid an entrance fee and ongoing rent for being there. The prison was notorious for the corruption of the gaolers working there who would extort as much money as possible from the prisoners, demanding high rents and mistreating and even torturing the individuals in their care. The prisoners did however have more freedom than in a normal prison, and records remain of debtors playing games whilst enjoying a beer, as they would have done in a public house. Prisoners were in the Fleet indefinitely though, as they needed to be able to pay off their debts before they could be released. William Hogarth immortalised the prison as part of his “A Rake’s Progess” series, where the main character himself fell into debt and was imprisoned.

This blog ends with a cliff hanger I’m afraid, as I will need to visit the National Archives at Kew and view the prison records in person to find out what happened to George next! I like to think that he was somehow able to get out of debt and return to his family, but this may not have been the case. His family is also a bit of a mystery as I have struggled to find death records for George’s wife or children. Did any of them leave London? We do know that one of George’s sons, Gabriel, also worked as a clockmaker, but he did not undertake an apprenticeship and there do not appear to be any records of any pieces bearing his name. Perhaps he worked alongside his father. George’s seventh child, my 7 x great grandfather, Ignatius Hobart (1721-?) lived in London but his son George Hobart (1746 – ?) moved to Kent where the family remained, eventually marrying into the Overy family two generations later. I will continue to chip away at the many “brick walls” I have come up against with the Hobart family and will update as and when I find out more!

Sources

Adele Emm, Tracing Your Trade and Craftsman Ancestors (Pen & Sword, 2015)

Claudius Saunier – The Watchmakers’ Handbook, 1881